Stark Threat on Medicaid

Pending case will test whether states can be held liable for providers’ violations

By Joe Carlson | August 10, 2013

From Modern Healthcare

For 20 years, the CMS has not applied the federal ban on physician conflicts of interest known as the Stark law to Medicaid claims. It’s focused on Medicare only.

For 20 years, the CMS has not applied the federal ban on physician conflicts of interest known as the Stark law to Medicaid claims. It’s focused on Medicare only.

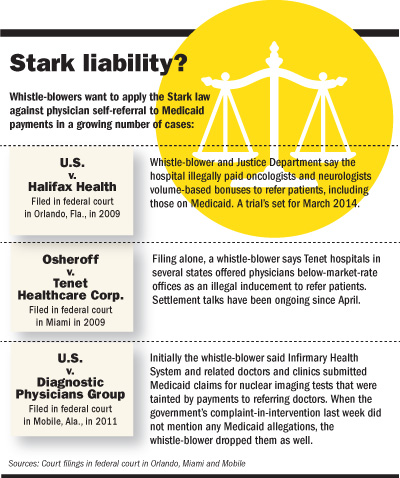

But private whistle-blowers have begun pressing for clarity on the issue because a 1993 law applying Stark to Medicaid remains on the books and could potentially put millions of dollars in their pockets. Now, the CMS says the law does apply, and the U.S. Justice Department is moving ahead by citing the previously unenforced law in a Florida lawsuit seeking repayment of Medicaid claims for Stark violations.

A spokeswoman confirmed last week in an e-mail to Modern Healthcare that the CMS does consider the Stark law applicable to Medicaid claims, even though it has never published final rules on how it would work.

If the Justice Department’s legal strategy holds, children’s hospitals may be the most affected because they treat so many Medicaid patients. But any hospital that cares for Medicaid patients could be affected. That may explain why organizations such as the Federation of American Hospitals deny that Stark applies to Medicaid.

Yet some legal experts say it is state governments—not the hospitals or doctors accused of wrongdoing—that may have to foot the bill if providers’ Medicaid claims violate the Stark law, because of the odd way that the original 1993 Stark law was written. That could create a sensitive situation at a time when the Obama administration is relying on states to expand their Medicaid programs under the healthcare reform law.

“The law doesn’t authorize (the federal government) to deny payment to the hospital. … The state is the one that loses the money,” said healthcare attorney Kevin McAnaney, who helped write the Stark rules as an HHS regulations lawyer. “That’s why it’s never been finalized.” The feds have “no stomach” for holding states responsible for providers’ financial misdeeds, he said.

In 1993, Congress expanded the scope of the Stark law from its original focus on stopping doctors from referring Medicare patients for laboratory services at facilities they own. It included doctors’ referrals for hospital services, among other things, and expanded Stark to cover Medicaid.

But Medicaid is run and partly funded by state governments. Rather than denying payments to Medicaid providers who violate the Stark law, the 1993 law directed the CMS to withhold from the state Medicaid program the federal matching portion of any claim that violates Stark.

At least that’s how the CMS officials read the law when they published proposed rules in the Federal Register in January 1998. Those rules were never finalized or implemented, and several experts said they were not aware of any case nationally in which a Medicaid provider has been successfully prosecuted for violating Stark.

“They came up with an idea and then never did anything with it,” said healthcare attorney Donna Clark of Baker Hostetler.

In the meantime, whistle-blower lawsuits in healthcare have taken off. In 2012, the Justice Department reported an all-time high of $3 billion taken back from pharmaceutical companies and healthcare providers via whistle-blowers’ lawsuits that later were joined by the Justice Department.

The insiders filing those cases stood to gain as much as 30% of each settlement, giving them a strong incentive to file as broad a lawsuit as possible for violations of the Stark law. Several healthcare legal experts said that pressure has caused the Justice Department to toss the CMS’ old reading of the law and try to squeeze healthcare providers for Medicaid repayments.

A massive Stark and False Claims Act lawsuit pending against Halifax Health and its medical staffing subsidiary in Daytona Beach, Fla., is the prime case. Federal prosecutors and a private whistle-blower say the system submitted more than 70,000 false claims, including some for Medicaid patients, reportedly creating potential penalties of as much as $1 billion because the system allegedly paid oncologists and neurologists based on the volume of business referred to the hospital.

The Medicaid allegations argued that the hospital, not the state Medicaid program, is liable for the damages because the providers induced the state to submit illegal claims.

Halifax lawyers disputed the broad allegations and said specifically that Medicaid claims were “a legal impossibility.” But U.S. District Judge Gregory Presnell in March 2012 refused to dismiss the Medicaid claims from the lawsuit. A March 2014 trial is scheduled.

“The impact is huge,” said Robert Fabrikant, a partner with Manatt, Phelps & Phillips. “There is a very substantial area of exposure that just didn’t exist before.” He noted that large Medicaid providers now may have a harder time convincing potential buyers in a hospital transaction that they don’t have potential legal exposure under Stark.

While it remains to be seen whether the Medicaid allegations in Halifax will withstand future court decisions, whistle-blowers aren’t waiting. Last month, the Justice Department announced it was joining a $500 million False Claims Act lawsuit against Infirmary Health System and a group of doctors and diagnostic clinics in Mobile, Ala. They are accused of using a profit-sharing arrangement to encourage unnecessary testing of patients, but the hospital denies the allegations, which originally covered Medicaid claims.

The whistle-blower dropped the Medicaid allegations, however, after the Justice Department declined to include it when it filed to intervene in the case last week. The whistle-blower’s attorney, Christ Coumanis of Coumanis & York in Daphne, Ala., said he knew the Medicaid claims would be a hard sell.

“Frankly, we weren’t sure if it would be something that would be enforceable under the False Claims Act,” he said.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!